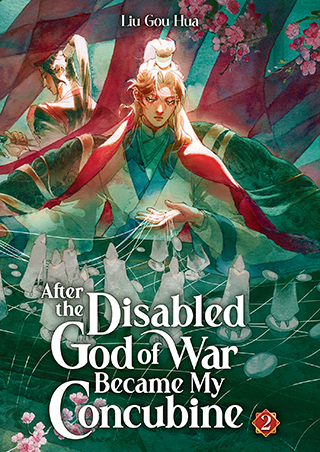

After the Disabled God of War Became My Concubine

History, Humiliation, and Healing: Why “After the Disabled God of War Became My Concubine” Reinvents the Transmigration Trope

In the vast landscape of Danmei (Chinese Boys’ Love) literature, the “transmigration” trope—where a modern character wakes up in a historical or fictional body—is a well-worn path. Usually, the protagonist is armed with a magical “system” or overpowering cheats. However, “After the Disabled God of War Became My Concubine” (残疾战神成了我的宠妾) by Liu Gou Hua offers a refreshing, grounded, and emotionally resonant twist on this formula. It replaces magical buffs with historical knowledge and replaces instant romance with a precarious game of political survival.

If you are looking for a story that balances heart-pounding court intrigue with a tender, slow-burn romance between two deeply intelligent men, this novel is your next obsession. Here is why this story stands out in the crowded genre of historical romance.

The Premise: When History Bites Back

The story begins with Jiang Suizhou, a modern-day history professor. He is rational, composed, and intimately familiar with the historical period of the “Jing Dynasty.” In his academic life, he criticized a student’s thesis for treating the legendary “God of War,” Huo Wujiu, as a figure of mere folklore.

Fate, it seems, has a sense of irony. Jiang Suizhou wakes up in the body of the Prince of Jing, a notorious “cut-sleeve” (a euphemism for homosexual) known for his cruelty and incompetence. The timeline? The exact moment the Prince accepts a “gift” from the corrupt Emperor: the captured, defeated, and crippled General Huo Wujiu.

In the original history, the Prince humiliates the General, treating him as a “pet concubine.” Three years later, when the General heals and restores his power, he exacts brutal revenge: beheading the Prince and hanging his head on the city walls for three years.

Jiang Suizhou’s goal is simple: Don’t get beheaded. To do that, he must tread a razor-thin line. He must maintain the Prince’s cruel persona in public to fool the Emperor while secretly nursing the General back to health in private.

The Characters: A Clash of Intellect and Will

Jiang Suizhou: The Reluctant Villain

Unlike many transmigration protagonists who are spunky or chaotic, Jiang Suizhou is refreshingly cerebral. He is a scholar first. His “cheat” isn’t magic; it’s his knowledge of the political landscape. He knows who the traitors are, he knows when the disasters will strike, and he knows exactly how dangerous Huo Wujiu is.

What makes him lovable is the contrast between his inner monologue and his outer actions. Internally, he is a fanboy of the historical General, respecting Huo Wujiu’s military genius. Externally, he forces himself to act the part of an arrogant, spoiled prince. This duality creates layers of tension—he saves Huo Wujiu not just out of fear, but out of a historian’s genuine respect for a hero who doesn’t deserve to die in filth.

Huo Wujiu: The Silent Storm

Huo Wujiu is the archetype of the “fallen hero,” but stripped of the usual angst-filled melodrama. Despite having his meridians severed and legs broken, he retains a terrifying aura of dignity. He doesn’t speak much, but his observation skills are lethal.

The beauty of his character arc lies in his shifting perspective. He expects torture and sexual humiliation. Instead, he gets… high-quality medicine? A custom-made wheelchair? A warm blanket? Huo Wujiu’s journey from “I will kill this man” to “Why is this man protecting me?” is a masterclass in slow-burn relationship development. He isn’t “tamed” by the MC; rather, he is “disarmed” by the MC’s confusing kindness.

The Unique Dynamic: The “Fake Concubine” Strategy

The title itself—After the Disabled God of War Became My Concubine—hints at the central conflict. In this world, the Emperor marries Huo Wujiu to the Prince as a form of ultimate insult: forcing a masculine God of War into the role of a female concubine for a gay prince.

However, the novel subverts this humiliation. Jiang Suizhou uses the “concubine” label as a shield.

- Publicly: He acts possessive and lecherous, claiming Huo Wujiu is his “favorite toy” so that no one else (like the Emperor’s assassins) can touch him.

- Privately: He treats Huo Wujiu with the utmost platonic respect, refusing to even sleep in the same bed unless necessary for the act.

This creates a delicious dramatic irony. The world thinks they are engaging in debauchery. Huo Wujiu thinks Jiang Suizhou is plotting something complex. Jiang Suizhou just wants to survive until Huo Wujiu recovers so he can peacefully retire (or flee). The comedy of errors that ensues—where Huo Wujiu begins to misunderstand Jiang Suizhou’s “protection” as “deep affection”—lays the foundation for a romance that feels earned, not forced.

Why It Appeals to Readers

1. The “Competence Porn”

There is a deep satisfaction in watching two competent people work. Jiang Suizhou handles the civil court, verbally sparring with corrupt officials and outsmarting the Emperor. Huo Wujiu, even from a wheelchair, influences the military and shadows. When they finally align, they are a power couple that dismantles their enemies with surgical precision.

2. Respectful Representation of Disability

While the “miraculous cure” is a staple of the Wuxia/Xianxia genre, the novel spends a significant amount of time dealing with the reality of Huo Wujiu’s condition. Jiang Suizhou doesn’t just magic the injury away; he deals with the logistics of accessibility, pain management, and the psychological toll of losing one’s mobility. The caretaking scenes are intimate and grounding, serving as the primary vehicle for their emotional bonding.

3. The “Face-Slapping” Justice

The villains in this story—specifically the corrupt Emperor and his cronies—are truly detestable. They are petty, cruel, and stupid. This makes their inevitable downfall incredibly satisfying. Watching Jiang Suizhou use his historical foresight to set traps for them, while Huo Wujiu prepares the physical blow, provides a cathartic release for the reader.

Conclusion

After the Disabled God of War Became My Concubine is more than just a catchy title. It is a story about how empathy can change history. It asks a compelling question: Can a man destined to be a villain change his fate by simply being decent?

For fans of Golden Terrace (Huang Jin Tai) or Qiang Jin Jiu, this novel offers a lighter but equally political flavor. It balances the heaviness of war and torture with the lightness of domestic fluff and misunderstanding-fueled humor.

If you want a romance where the “I can fix him” trope is replaced with “I will respect him until he fixes himself (and then protects me),” this novel is a must-read. Jiang Suizhou and Huo Wujiu prove that sometimes, the best way to survive history is to rewrite it together.